In our only episode for August, we bring you an interview with Professor Miller Goss about pioneering Australian radio astronomer Ruby Payne Scott, the latest astronomical news, what you can see in the August night sky, and your feedback.

The News

In the news this month:

- In breaking news it has been reported that the long-awaited eclipse of the star e Aurigae has begun (S&T). Most eclipsing variables are caused by two stars in orbit, periodically blocking each other's light, but in the case of epsilon Aurigae the eclipsing object is thought to be a long thick disk of gas, possibly containing stars hidden in the dense material. Spectroscopic observations by Robin Leadbeater, an amateur astronomer in the UK, have shown changes in the spectrum which could be due to the leading edge of the eclipsing cloud as it crosses in front of the star. If this is the case, then as the eclipse progresses, the star will begin to fade as thicker parts of the cloud move across our line of sight. Eclipses in this system occur every 27.1 years, and the star is predicted to fade from its normal magnitude of 3.0 down to 3.8 by the end of the year. Amateur astronomers interested in variable stars are encouraged to make their own observations and send their results to the AAVSO.

- Using telescopes high on the islands of Hawaii, astronomers have detected light from supernovae which occurred roughly 11 billion years ago, smashing the previous distance record for such objects. Led by Jeff Cooke, a cosmologist at the University of California, the team used a new technique to look for the tiny change in brightness of a distant galaxy due to a stellar explosion. They were looking for the signatures of a class of explosion known as type IIn supernovae, caused by stars between 50 and 100 times as massive as the Sun. These stars are different because they shed a large amount of material before they die. When the final catastrophic explosion occurs, the remaining material and the resulting shock wave plough into the surrounding gas previously expelled from the star, resulting in a remnant so bright that it is still visible many years after the event. Because these type IIn supernovae are the brightest class of stellar explosion, they are the most likely to be detected at large distances.

The normal method of searching for supernovae is to compare two images of the same galaxy taken on different nights and look for new objects in the image. While this technique works well for nearby galaxies where supernovae will appear relatively bright, it becomes increasingly difficult in more distant galaxies. Rather than looking at individual images taken on single nights, Cooke's team took five years of images covering four separate patches of sky and stacked them together creating one composite image per field for each year of observation. By comparing the brightnesses of each galaxy in the stacked images, the astronomers identified four potential supernovae. They then used the Keck telescope to observe the spectra of each of the candidates, using the light collected to determine the object's composition and distance. This follow-up work showed that three of the candidates were supernovae, two of which occurred more than 11 billion years ago, beating the previous record by 2 billion years.

The results were published in the 9th July issue of the journal Nature where the authors suggest that using this method with planned synoptic surveys on 8-m class telescopes could identify an estimated 40,000 type IIn supernovae at this distance, as well as even older explosions caused by some of the first stars created following the Big Bang, probing stellar processes all the way back to the very early universe. - Among the brightest and most energetic objects in the universe are so-called Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN). These are objects outside the Milky Way, thought to be powered by material falling onto supermassive black holes in the centre of other galaxies. The process can create powerful jets which can accelerate particles up to very high speeds and generate very high energy gamma-ray emission. Although astronomers have known for some time that these AGN are bright sources of gamma-rays, they did not know exactly where in these galaxies the high energy emission originated. But in research published in the online edition of Science magazine on the 2nd July, a collaboration of more than 350 scientists has finally narrowed it down.

High energy emission from the nucleus of the active galaxy M87 was first detected in 1998, and gamma-ray outbursts have since been confirmed by the HESS, VERITAS and MAGIC telescopes located in Namibia, Arizona and La Palma respectively. All of these experiments are gamma-ray detectors which pick up this high energy emission, but do not have sufficient resolving power to accurately determine the location of the outburst within M87's core. Located 50 million light years away, M87 is the largest galaxy in the Virgo cluster and contains a central black hole six billion times as massive as the Sun.

In order to determine the source of the gamma-rays, the HESS, VERITAS and MAGIC collaborations teamed up with astronomers using the Very Long Baseline Array - a collection of ten radio telescopes spread across North America from Hawaii to the Caribbean. By linking widely separated radio telescopes together, astronomers can synthesise a much larger telescope, resulting in images with much finer detail. Using all four instruments, HESS, VERITAS, MAGIC and the VLBA, the team monitored M87 over 50 nights between January and May 2008. As well as detecting gamma ray flares, the observers also detected large flares of radio waves from M87. Using the VLBA's high resolution they determined that these flares were occurring at the same time as the gamma ray flares and were being generated in a region very close to the black hole where material falling in forms a tightly rotating torus known as an accretion disk. The observations show that the high energy emission is coming from an area no larger than 50 times the size of the black hole's event horizon - the area within which matter cannot escape from the black hole. For the black hole in M87, this is a region roughly twice the size of the solar system. - Using state of the art techniques, two teams of astronomers have obtained the sharpest ever images of the supergiant star Betelgeuse. The second brightest star in the constellation of Orion, Betelgeuse appears red even to the naked eye, and is one of the largest stars known, almost 1000 times larger than the Sun. It is a type of star known as a red supergiant and is so enormous that if it were placed at the centre of the solar system, its surface would lie almost at the orbit of Jupiter. Stars this massive run out of fuel much quicker than smaller stars like the Sun, and eventually explode as supernovae.

There are still some unanswered questions about red supergiants, one of which is how they shed material. These stars can lose as much material as is contained in the entire Sun in just 10,000 years, but the mechanism by which this occurs is not well understood. But in work accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, two independent teams using ESO's VLT have made observations which might provide some answers.

The first team used adaptive optics which attempts to correct for the fluctuations in the Earth's atmosphere which make stars appear to twinkle. They combined this with another technique known as "lucky imaging" where only the sharpest exposures are combined to produce a high resolution image in a similar way to imaging with a webcam through a backyard telescope. The resulting images are so sharp that they could detect a tennis ball at the distance of the International Space Station. The team's images of Betelgeuse show a large plume of gas extending out from the star to more than six times the radius of the star itself, showing that it is not shedding material evenly in all directions.

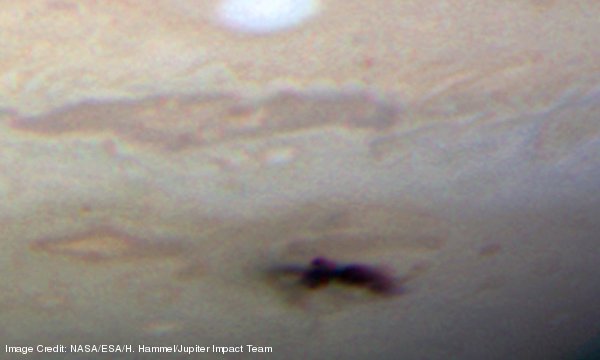

Meanwhile, the other team used the VLT interferometer, which combines the light from three telescopes to produce results with much greater resolution. Using this technique, the second team were able to indirectly detect features up to four times smaller than the other teams images, allowing them to study the surface of Betelgeuse. They found that the gas in the star's atmosphere is moving up and down in giant bubbles like huge convections cells almost as large as the star itself. Together, these two superbly detailed observations suggest that it is these large scale motions in Betelgeuse's atmosphere which are responsible for producing the giant plumes of material. - Almost exactly 15 years after astronomers around the world watched as fragments of the comet Shoemaker-Levi 9 hit Jupiter, leaving black scars on the planet's cloudy surface, an amateur astronomer caught images of another impact on the gas giant. First imaged on July 19th by Anthony Wesley in New South Wales, Australia, news of the impact rapidly spread around the world. Within hours, several observers had confirmed the new black blemish on Jupiter's surface, and within days it had been imaged by the Keck telescope and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii. The infra red observations showed that the scar was warm, indicating as upwelling of material in the planet's atmosphere, probably caused by an impact. Even the recently upgraded Hubble Space Telescope was used to image the event, despite commissioning of the new instruments not being complete. The Hubble image was the first science observation carried out with the newly installed Wide Field Camera 3 and shows the instrument is performing well. The most recent images of the impact site show that the black spot is evolving and now contains two nuclei, probably due to the high winds and complex dynamics in Jupiter's dense atmosphere.

By coincidence, another amateur astronomer, Frank Melillo of New York in the USA, spotted a new feature in the atmosphere of Venus on the same day. The Venus Express spacecraft in orbit around the planet confirmed that the spot had first appeared four days earlier. Observations in the ultra violet suggest that this feature was not caused by a meteorite impact and various suggestions have been put forward, such as a volcanic eruption, or a concentration of charged particles from the Sun, but as yet it is not known exactly what caused it.

A profile of Ruby Payne Scott

Professor Miller Goss (NRAO) describes the life and work of pioneering Australian radio astronomer Ruby Payne Scott.

Payne-Scott had a remarkable career at CSIRO as a radio astronomer due to her participation at the Division of Radiophysics where she worked on the development of World War II radar. She and Joseph L. Pawsey carried out an initial radio astronomy experiment in March 1944 from the Madsen Building on the Sydney University grounds. In 1945, Payne-Scott carried out some of the key early solar radio astronomy observations at Dover Heights (Sydney). In the years 1945 to 1947, she discovered three of the five categories of solar bursts originating in the solar corona and made major contributions to the techniques of radio astronomy. Solar bursts represented large, rapid increases, at the time scale of seconds, of radio emission from the solar corona usually observed at low radio frequencies.

Payne-Scott had a remarkable career at CSIRO as a radio astronomer due to her participation at the Division of Radiophysics where she worked on the development of World War II radar. She and Joseph L. Pawsey carried out an initial radio astronomy experiment in March 1944 from the Madsen Building on the Sydney University grounds. In 1945, Payne-Scott carried out some of the key early solar radio astronomy observations at Dover Heights (Sydney). In the years 1945 to 1947, she discovered three of the five categories of solar bursts originating in the solar corona and made major contributions to the techniques of radio astronomy. Solar bursts represented large, rapid increases, at the time scale of seconds, of radio emission from the solar corona usually observed at low radio frequencies.

In a remarkably short period, Payne-Scott played a key role in the rapid growth of radio astronomy in the immediate post war environment. She provided scientific leadership during the period as well as technical insights. In her seven years as a radio astronomer (1944-1951), she made monumental contributions to this new science in which Australia excelled and helped lay the foundations for many future decades of world leadership in radio astronomy.

Miller's book - "Under the Radar - The Life and Times of Ruby Payne Scott, pioneer female radio astronomer" - will be available on Amazon later in the year. It should hopefully also be available via your local library service.

The Night Sky

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the night sky during August 2009. This month, on the night sky pages, the images of the month show LRO images of the Apollo landing sites. It is also worth visiting the Lunar World Record 2009 and Google Moon.

Northern Hemisphere

Leo is setting in the glare of the Sun but it is still just possible to see Saturn and then Mercury in the first few weeks. Higher up is the constellation of Bootes. Just to the left of Bootes is Corona Borealis - the Northern Crown. Moving up towards the south you'll see the constellation of Hercules. It has four stars making up the keystone. Looking up the right hand side of the keystone you'll see globular cluster M13. Below Hercules is Ophiuchus and below that is Scorpius with its lovely red star Antares. To the left is the constellation of Sagittarius - The Archer - which does look like a rather nice representation of a teapot. Where the liquid would leave the spout, with binoculars you might see the little fuzzy glow of open cluster M7. Above the teapot is the Lagoon Nebula. Over to the east in the sky you'll see the lovely region of the Summer Triangle with Aquila, Lyra and Cygnus.

The Planets

- Jupiter, now lying in Capricornus, becomes more easily visible this month rising soon after twilight. During August its magnitude remains pretty constant at -2.8 as, on August 14th, Jupiter is at opposition - that is opposite the Sun and so approximately due south at midnight - and thus its distance from us does not change that much during the month. It has an angular size of 48 arc seconds so a small telescope will show much detail on the surface if seeing conditions are good. It will lie to right of the almost full Moon on the 6th of August.

- Saturn is just be seen seen as twilight deepens lying in Leo - but somewhat below the main body of the Lion. You will need a very low western horizon to spot it though! Its magnitude is +1.1 - not as bright as usual, with Saturn significantly less bright this year than it sometimes is: the rings are very close to edge on and thus there is less apparent reflecting area. At the beginning of August they are at an angle of just 1.9 degrees from the line of sight! This narrows to during the month as they will be edge on to the Earth on September 4th. However they are edgewise on August 10th so it might be posible to see that they have turned from bright to dark! Those with a computer controlled telescope might be able to pick up Saturn whilst it is higher in the sky before the the sky darkens significantly. It will not be until 2016 that they will be at their widest again. A small telescope will easily show its largest moon, Titan, and show some bands around the surface.

- Mercury may be seen, probably with the help of binoculars, low in the west but in bright twilight. It dims from magnitude -0.4 to magnitude +0.4 during the month. It will lie just 0.6 degrees above the star Regulus in Leo on the 2nd of August and passes 3 degrees from Saturn on the 26th, but I suspect that both planets will, by then, have been lost into the glare of the Sun.

- Mars is becoming more prominent in the pre-dawn sky this month as it rises just after midnight and will be seen in the east before dawn. It has a magnitude of +1. Its angular size will increase from 5.3 to 5.8 arc seconds during the month so, under ideal seeing conditions, a telescope might begin to show some of the more prominent features such as Syrtis Major. We will have to wait a month or so until it will be seen more easily as the nights get longer and it rises earlier in the night! The Earth will, of course, be overtaking Mars "on the inside track" so we will come closer to it and its angular size will increase so allowing more features on the surface to be seen.

- Venus is moving increasingly further away from the Sun and by mid month will be 27 degrees above the eastern horizon by sunrise. A small telescope will show a waxing gibbous disc dropping from 14.8 arc seconds in diameter to 12.6 arcseconds as it moves towards the far side of the Sun. It magnitude drops from -4 to -3.9 during the month.

Highlights

- If you observe Jupiter in the first week of August you may be surprised to observe 5, not 4, Galilean moons! There is an interloper, the +5.9 magnitide star 45 Capricorni, which is only just fainter than Callisto. If you have a telescope of 6 inches or more, you may well see that whilst the satellites of Jupiter appear as tiny discs, the star will look pointlike. As Jupiter passes westwards across the sky it will occult (pass in front of) the star at 23:52 BST on August 3rd. 45 Capricorni will emerge almost two hours later at 02:00 BST on the morning of the 4th August.

- Full Moon occurs just after midnight on August 6th. This is, of course, when eclipses of the Moon can occur and this month there is a penumbral eclipse when the lower third of the Moon will lie in the partial shadow of the Earth and so will appear somewhat dimmer and have a flatter, dull grey, tone.

- During the first two weeks of August, Saturn may still be seen low above the western horizon just after sunset. You may well not observe any rings as, on August 9th, they are edge on to the Sun and will thus not be illuminated! Thereafter the rings are tilted so that they will be illuminated on their other side from us and not be directly visible. One will observe a thin dark line bisecting Saturn which is partly a silhouette of the rings and partly their shadow on Saturn's surface. Sadly Saturn, by then, will be increasingly lost in the glare from the Sun.

- If it is clear on the 11th and 12th of August, one will have a chance of seeing the meteors in the Perseid Meteor Shower - the year's most dependable meteor shower. It is not, perhaps,the best year to observe the Perseids as a waning gibbous Moon will be rising in the north-east and its glare will obscure the fainter meteors. Look up towards the North-East from 11 pm onwards on the nights of August 11th, 12th and 13th and 14th. After midnight, as Perseus rises higher into the sky, the numbers seen may well rise too! Most meteors are seen when looking about 50 degrees away from the "radiant" (the point from which the meteors appear to radiate from) which lies between Perseus and Cassiopea. (See the star chart below) The Perseid meteors are particles, usually smaller than a grain of sand, released as the comet Swift-Tuttle passes the Sun. The shower in quite long lived, so it is worth looking out any night from the 10th to the 15th of August. This last day could well be the best as the Moon will be rising later and be less bright.

Southern Hemisphere

Looking north at about 8pm in mid-August you have a lovely view of the Milky Way arcing high overhead. Below Sagittarius we have Aquila the Eagle and lower in the north east is Lyra. Down to the right of Aquila is Delphinus the dolphin. Looking towards the south there is the Milky Way dropping down to the south west. There are the constellations of Centaurus, Crux, Musca, Vela and Carina - a very rich part of the Milky Way. Fairly low in the sky is Vela which has a fairly large cross of stars that is often confused with the smaller Southern Cross. Almost due south is the Large Magellanic Cloud and up to the left of that is the Small Magellanic Cloud with globular cluster 47 Tucanae just above. To the right of LMC is the Tarantula Nebula (30 Doradus).

Odds and Ends

NASA's Near-Earth Object Program Office at JPL have launched Asteroid Watch to keep us up-to-date on objects which could be a threat to Earth. You can subscribe to their RSS feed, sign up to email updates and even follow them on Twitter.

At London's Science Museum, an exhibition has just opened titled "Cosmos & Culture: how astronomy has shaped our world". The exhibition is free and features various exhibits including a Moon map by Thomas Harrison.

Jesper Johag wrote in to tell us about a Swedish radio broadcast called "Space Age Questions" (MP3) from December 1959. It starts in Swedish but features and interview with Sir Bernard Lovell at about 28 minutes in.

David Burden told us that he had created a Tranquility Base simulation in Second Life which overlays the moon terrain with the maps of where they walked, and keys in the photographs and video to the places they were taken.

Show Credits

| News: | Megan Argo |

| Noticias en Español - Agosto 2009: | Lizette Ramirez |

| Interview: | Prof Miller Goss and Stuart Lowe |

| Night sky this month: | Ian Morison |

| Presenters: | David Ault, Jen Gupta, Stuart Lowe and Neil Young |

| Editor: | Stuart Lowe |

| Intro: | David Ault and Jack Ward |

| Segment voice: | Danny Wong-McSweeney |

| Website: | Stuart Lowe |

| Cover art: | Hubble Space Telescope image of Jupiter collision Credit: NASA/ESA/H. Hammel/Jupiter Impact Team |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Noticias en Español - Agosto 2009 [Duration 11:22]:

Noticias en Español - Agosto 2009 [Duration 11:22]: