This time around, we talk to Dr Lucie Green about Solar activity and Dr Paul Woods tells us about a sweet molecule in space. Megan rounds up the latest news and we find out what's in the February night sky from Ian Morison and John Field.

The News

In the news this month: January saw the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), termed the 'Superbowl' of astrophysics events. January's highlights included dark matter, exoplanets, black hole burps and star formation.

The conference saw the unveiling of what is so far the largest dark matter map of the Universe available. The map covers more than one billion light years. Dark matter itself is invisible, but the map-makers (the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Lens Collaboration) used gravitational lensing to detect the locations of dark matter clumps. Gravitational lensing is the bending of space-time by anything with mass (which dark matter has!), which in turn causes light to bend around these 'etched out' regions of space-time. The light being bent, in the case of this map, came from ten million distant galaxies.

The map shows that large-scale dark matter is clumped into blobs, which are connected by thin filaments. The nature of the dark matter geometry can reveal some of its intrinsic properties and so, with the help of this map, we are getting closer to shedding some light on the dark matter puzzle.

For many years it has been commonly accepted that nothing can escape from the clutches of a black hole. However, evidence of a black hole 'burp' was presented at this year's AAS meeting. Observations by NASA's Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer and an array of radio telescopes known as the VLBA, witnessed a black hole releasing jets of plasma in June 2009. These jets of ionised gas in turn push particles outwards from the accretion disc of the black hole and send them off into space, escaping the clutches of the black hole.

Bubbles of hot gas in space are believed to be the hub of medium-sized star formation, just like the kind of environment thought to have created the Sun some five billion years ago). One such modern local stellar nursery, in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), is believed to contain many bubbles of hot gas. This is surprising, since the LMC itself is mostly cold gas with a mass millions of times larger than that of the sun. However, within this cold gas live massive stars which heat the gas around them, forming these hot bubbles. The bubbles are then pushed from the massive stars via hot winds, similar to warm and cold fronts in our own Earth's weather.

And finally: The increasingly popular search for extrasolar planets has revealed a happy piece of news for all you alien enthusiasts. According to the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, the average star hosts around 1.6 planets, so, with an estimated 100 billion stars in the Milky Way, there could be around 160 billion possible environments where we can search for new friends.

It was also determined that the majority of these planets would be small and rock-like, very similar to the Earth, so we may even have a hope of recognising whatever, or whoever, we find.

Interview with Dr Lucie Green

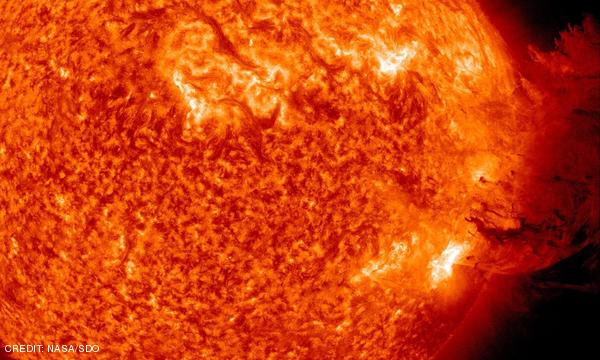

Dr Lucie Green is a Solar physicist at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory. Jen caught up with Lucie to find out what she's been working on since her last appearance on the Jodcast. In this interview, Lucie talks about her work studying coronal mass ejections from the Sun. She explains how these phenomena interact with the Earth's magnetic field to cause the aurorae and talks about some of the telescopes she uses to study the Sun.

Interview with Dr Paul Woods

Dr Paul Woods from University College London talks to us about the formation of simple sugar in space. This molecule was detected in star-forming regions and molecular clouds, and may have accumulated on cold dust grains in the interstellar medium before being evaporated into gas by newborn stars. Larger molecules may be detected in the future, bridging the current observation gap between the simplest molecules and the much larger fullerenes.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during February 2012.

The constellation of Orion takes centre stage with its bright stars, Betelgeuse and Rigel. Orion's Sword contains M42, the Orion Nebula, visible as a hazy glow through binoculars. Sirius, our brightest night-time star, is down and to the left; atmospheric scintillation makes it twinkle colourfully. Above and right of Orion is Taurus the Bull, containing the red star Aldebaran as its eye and the Hyades Cluster, which forms its head. The Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, are nearby. Up and left of Orion is Gemini, containing the Heavenly Twins, Castor and Pollux, while Auriga is towards the zenith with its bright star Capella. The Milky Way runs through Auriga and hosts several open star clusters. Leo the Lion rises in the east later in the evening, above the planet Mars.

The Planets

- Jupiter is at its highest (about 50°) around sunset, shining at magnitude -2.4 in Aries. With an angular size of 38.7", a small telescope will show its equatorial bands and Great Red Spot.

- Saturn is up from late at night until morning, reaching 31° elevation. It brightens from +0.6 to +0.5 during the month and its rings continue to open to our line of sight, reaching 15° from edge-on and allowing the gaps between sets of rings to be seen.

- Mercury passes behind the Sun (superior conjunction) on the 6th, but reappears near month's end, shining at magnitude -1.1 after sunset in the south-western sky. Its angular size is around 6" and is increasing.

- Mars moves westwards in the sky from night to night, contrary to the usual apparent planetary motion; this is called retrograde motion, and results from the Earth overtaking it on the inside track as the two planets orbit the Sun. Its angular diameter is increasing and, at the end of the month, it is 14" in size, rises by 6pm and reaches 50° elevation. Surface features can be seen using a small telescope, including Syrtis Major and the north polar cap.

- Venus is about 30° above the south-western horizon at sunset at the beginning of the month and 37° above by the end, as it increases its angular separation from the Sun. Its angular size increases over the month from 15 to 18" as its illuminated fraction drops from 74 to 64%, giving it a very bright and constant magnitude of -4.1.

Highlights

- Comet Garradd can be seen in the east before dawn this month. The globular cluster M13 is nearby, above the Keystone, which is the asterism consisting of the four brightest stars in the constellation of Hercules. It is the best-seen globular cluster in the northern hemisphere, and the cluster M92 is not far away, to the left of the Keystone. The two are at magnitudes of +6 and +6.5 respectively, and the magnitude +7 comet makes its closest appearance to M92 on the 3rd, allowing it to be found with binoculars.

- Mars can be seen close to a waning gibbous Moon at around 9pm on the 9th.

- Saturn makes a near-straight line in the sky with a waning Moon and the star Spica before dawn on the 12th.

- Jupiter, Venus, Mercury and a thin crescent Moon are all in close proximity early on the evening of the 25th. You should be able to see Earthshine, otherwise known as 'the old Moon in the new Moon's arms'. The Hyginus Rille is a nice feature of the Moon to look at around the middle of this month. It appears in the Mare Vaporum as a line with an 11-km crater in the centre, which is probably the result of a volcano during the Moon's early history.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during February 2012.

Three planets are visible in the evening sky: Venus, which sets in the west after sunset, Jupiter, which sets in the north-west around midnight, and Mars, which rises red in the north-east after twilight.

The brightest star in the night sky, Sirius, sits high in the north in the constellation of Canis Major, the Large Dog. Towards the northern horizon is Procyon, the eighth-brightest night-time star, in the constellation of Canis Minor, the Little Dog. The two dogs accompany Orion, the Hunter, while between them is Monoceros, the Unicorn. It contains a number of beautiful stars, including the triple system Beta Monocerotis, which can be separated in a telescope, and the double star Epsilon Monocerotis, with its yellow and blue components. The constellation also offers a number of star clusters as it is on the edge of the Milky Way. Between Sirius and Procyon is M50, also designated NGC 2323, a cluster of about 100 stars that is visible in binoculars. To the north-east of Monoceros is NGC 2232, an irregular open cluster, while the bright, scattered cluster NGC 2244 sits in the centre of the Rosette Nebula. Other interesting clusters include NGC 2261, NGC 2301 and NGC 2264, the last of which is also called the Christmas Tree Cluster due to its shape. It contains the Cone Nebula at its tip, which can be seen through a large telescope. Monoceros is also home to the massive 6th-magnitude binary system Plaskett's Star, which has a mass of around 100 times that of our Sun. The 15th-magnitude star V838 Monocerotis has variable brightness, but is usually very faint. Other well-known variable stars include Beta Persei (Algol), which varies because it is an eclipsing binary system, and Betelgeuse, which swells and cools as it nears the end of its life.

In the south-east is Crux, the Southern Cross, and near to that is Musca, the Fly, with the Coalsack Nebula joining the two. The star Alpha Muscae is a double that can be split with a medium-sized telescope. Theta Muscae is also a double, and the brighter of the two partners is a Wolf-Rayet star, meaning that it ejects a lot of material. Nearby are the globular clusters NGC 4372 and NGC 4833 and the 10th-magnitude planetary nebula NGC 5189, which has an S-shaped appearance.

Highlights

- Two meteor showers, known as the Centaurids, occur in early February, producing 5-25 meteors per hour. The Moon will hamper their observation this year, however.

- The constellations of Orion, Taurus and Gemini are visible this month, but will soon slide away into the twilight sky.

- The Milky Way runs almost from north to the south in the evenings this month, with the constellation of Carina and its bright star Canopus overhead. There are many star clusters and nebulae to be found with binoculars in this region of the sky.

Odds and Ends

The High Frequency Instrument (HFI) aboard ESA's Planck space telescope concluded its two-and-a-half-year observation of the Cosmic Microwave Background in January. Planck has been mapping "the oldest light in the Universe" all across the sky with unprecedented precision in sensitivity, resolution and the lowest temperature possible. Inevitably, its coolant finally evaporated, ending its useful life. Planck's Low Frequency Instrument, however, will continue observations for the remainder of 2012, with the results of the mission being released shortly thereafter.

Astronomers from the University of Pittsburgh worked out the colour of the Milky Way as seen from the outside, and announced their result at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. They used observations of other, similar galaxies to avoid the problem of dust, which obscures the view of our own galaxy from the inside. The result was a galaxy declining in star formation rate, neither particularly red nor strikingly blue, with a colour spectrum corresponding to white light from an object at a temperature of about 5000 Kelvin. The team provided an image of a comparable galaxy for reference, and colourfully described the hue of the Milky Way as "being very close to the light seen when looking at spring snow in the early morning, shortly after dawn".

Entries are now being accepted for the Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition, run by the Royal Museums Greenwich. If you think you can match last year's winners, why not enter?

The Phobos-Grunt spacecraft crash-landed harmlessly into the Pacific Ocean on the 15th of January. Originally bound for a return trip to the Martian moon Phobos, the probe was beset by communication problems and failed to leave Earth orbit, eventually succumbing to atmospheric drag and being destroyed by re-entry and final impact. A piggybacking Chinese Mars orbiter, Yinghuo-1, was lost along with it.

The International Telecommunication Union has decided to delay its verdict on the leap second debate until 2015. The leap second is a time adjustment which has been used 24 times since 1972, and will be used again later this year. Co-ordinated Universal Time (UTC) is measured using precise atomic energy transitions, but our times of day and night get out of sync with this atomic time as the Earth's rotation very gradually slows down. The addition of leap seconds to UTC compensates for this, but can be an annoyance to those who rely on highly accurate timekeeping over long periods, since they must keep track of all the adjustments. Should we abandon the leap second and pledge allegiance to the atomic clock, or should we keep pinning our time standard to the Earth's rotation?

Show Credits

| News: | Megan Argo and Mel Irfan |

| Interview: | Dr Lucie Green and Jen Gupta |

| Interview: | Dr Paul Woods and Melanie Gendre |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | Adam Avison, Melanie Gendre, Libby Jones and Mel Irfan |

| Editors: | Melanie Gendre, Megan Argo, Adam Avison, Claire Bretherton and Dan Thornton |

| Segment Voice: | Kerry Hebden |

| Website: | Mark Purver and Stuart Lowe |

| Producers: | Libby Jones and Mark Purver |

| Cover art: | A coronal mass ejection from the Sun, as seen by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. CREDIT: NASA/SDO |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]