This month we bring the final interviews from JENAM, a round-up of current space missions, news about the anniversary of the 1919 eclipse, what you can see in the night sky, and the latest astronomy news.

The News

In the news this month:

- Fast-spinning radio pulsars with millisecond rotation periods are thought to be the result of a process involving the transfer of material from a companion low-mass star onto a normal pulsar. This accretion process adds mass and angular momentum to the pulsar resulting in its rotation rate speeding up and the emission of X-rays. Using telescopes around the world, a team of astronomers has for the first time discovered evidence of this process taking place.

Pulsars are extremely dense neutron stars, left over after massive stars explode as supernovae. They have strong magnetic fields which generate beams of light and radio waves which sweep across the sky as the pulsar spins. Most pulsars rotate a few times a second, but some, known as millisecond pulsars, rotate hundreds of times a second. Ordinary pulsars in a binary system with a low-mass companion can start to accumulate material in an accretion disk - a flat spinning ring of material around the pulsar. While this disk exists, it is thought that the radio waves characteristic of a pulsar would be quenched and the object would not appear as a pulsar. When the rate of infalling material slows down and stops, the pulsar's emission would be able to disrupt the accretion disk, blowing material out of the system and allowing the radio emission to resume. Now, a team led by Anne Archibald at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, have found evidence of this process taking place in a binary star system 4000 light years away.

A millisecond pulsar was discovered in the system in 2007, so the team looked back through archive data from several telescopes. What they discovered was a dramatic change in the system over the last decade. Optical observations in 1999 showed a Sun-like star, while observations a year later showed evidence of an accretion disk around the neutron star. By 2002, the evidence for this disk had disappeared. The observations in 2007, made with the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, found a millisecond pulsar spinning 592 times per second. The researchers say that this system appears to be the missing link between millisecond pulsars and accreting binary systems known as Low Mass X-ray Binaries. The results were published in the journal Science during May. - Models of solar system formation show that comets form at large distances from their parent star. This makes sense as they are made up largely of frozen material, but a long-standing mystery is how they end up containing tiny silicate crystals which need very high temperatures to form. These crystals start out in an amorphous form where their atoms are arranged randomly. At high temperatures, the atoms in these crystals become more ordered, forming what is known as a crystalline lattice. Because they need high temperatures to form, these crystalline silicates were not expected to be found in comets, so how they come to be there is a puzzle. In the May 14th issue of Nature, a team led by Peter Abraham of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, published the first evidence of the formation of crystalline silicates in the disk around a young sun-like star. Together with colleagues from Leiden Observatory and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Abraham used the Spitzer Space Telescope to observe the eruptive star EX Lupi in April 2008 during one of its outbursts. When they examined the spectra from these observations, the researchers discovered the infrared signature of silicate crystals in the disk of dust and gas around the star.

When they compared their results to similar spectra of EX Lupi taken between outbursts, they found that the older observatories only showed the presence of amorphous silicates rather than the crystalline form. In the newer observations taken during the star's outburst, a broad peak corresponding to amorphous silicates was present, but an additional narrow peakat a wavelength of 10 microns was also visible. This narrow feature is likely caused by the presence of forsterite, the magnesium-rich crystalline form of the mineral olivine.

The appearance of this additional feature in the spectrum during the star's outburst suggests that crystal formation was happening in the star's disk during the outburst. The researchers think that this is the first time ongoing crystal formation has been observed. They say that the crystals were probably formed on the surface layer of the star's inner disk by heat from the outburst, in a process known as thermal annealing where a substance is heated to a temperature where some some of its bonds break and then re-form altering the material's structure and physical properties. The forsterite crystals detected are just like those found in comets in the solar system which could have been produced by similar outbursts from out own Sun when it was much younger. - There has been much speculation over the cause of an excess of cosmic-ray electrons and positrons recently detected by the ATIC and PAMELA experiments. Suggested sources of this excess not only include Galactic pulsars and supernova remnants, but also more exotic explanations such as dark matter annihilations. Now, new results from the Large Area Telescope, or LAT, on board the Fermi satellite have added new information to the puzzle.

Models of cosmic ray electrons and positrons interacting with the interstellar medium predict a featureless distribution in the number of particles with energies between 10 and a few hundred giga electron volts. However, last year the European satellite PAMELA detected surprisingly large quantities of high-energy positrons, while the balloon-borne ATIC experiment found a significant peak in the total electron plus positron count at high energies. Like ATIC, the LAT on Fermi is sensitive to the total electron plus positron flux. The new results from Fermi, published in the journal Physical Review Letters on the 4th of May, do show a larger number of particles with energies of around 500 giga electron volts, but the excess is no where near as large as that measured by the ATIC experiment. The new results are, however, consistent with the excess of positrons seen by PAMELA.

While these Fermi observations are the most precise yet at these energies, they are still not enough to either confirm or rule out a particular origin for these high energy particles. The LAT team are planning further observations to reduce the uncertainties and hopefully determine whether the particles are caused by dark matter annihilations or known local sources of electrons such as pulsars and supernova remnants. - May was a busy month in space with the successful launch of two space telescopes and a servicing mission to Hubble. On the 11th of May, the space shuttle Atlantis took off on the fifth and final flight to service the Hubble Space Telescope. During the 13-day flight, the crew carried out five spacewalks totalling 36 hours and 56 minutes, successfully installed the Wide Field Camera 3 and the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph, and repaired both the Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph. The astronauts also replaced all six of Hubble's batteries launched with the telescope in 1990 and now losing capacity as they age. Other tasks included replacing the fine guidance sensors and all six rate sensor units - the gyroscopes essential to keep the telescope pointing in the right direction. The upgrades will hopefully allow the telescope to keep functioning until 2014 when the James Webb Space Telescope is scheduled to launch.

May 14th saw the successful launch of the Herschel and Planck satellites, lifting off together on board an Ariane 5 rocket from the European Space Agency's launch site in French Guiana. Planck is a telescope designed to map the tiny fluctuations in the Cosmic Microwave Background in unprecedented detail, while Herschel is an infrared telescope which will study some of the coldest objects in the Universe. Once in space, the two satellites separated from each other in order to travel independently out to a point known as L2 - a gravitationally stable orbit one and a half million kilometres on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun. Both satellites are undergoing in-flight tests and are so far functioning perfectly.

The Variable Sun

Prof Mike Lockwood (University of Southampton) talks to us about the Sun. Mike starts by describing how the Sun's output waxes and wanes on an 11 year timescale. The cycle is related to the Sun's magnetic field and from sunspot records we know that this cycle is by far the normal behaviour of the Sun over the last few millenia. On top of the 11 year activity cycles there are longer cycles. The Sun's variability is seen in records of our climate and shows up in Grand Maxima, Minima and ice ages. Lower solar activity generally means lower average disruption to satellites and power systems and these should decline as we leave the current maxima. However, there is evidence that the biggest single outburst events occur at times of middling activity. The entire space age has occured within a grand maxima of solar activity - a cycle in the top 10% of activity - and we have never been a high-tech society in a time of middling activity before. The conversation ranges from global warming, to ESA's Ulysses and late nights in the library.

These are strange and exciting days for solar physicists.

Gamma ray astronomy

Neil interviewed Dr Jim Hinton (University of Leeds) about high energy astronomy. Most high-energy astronomy is done with satellite based detectors because the Earth's atmosphere is opaque to the gamma rays. From the ground it is possible to detect the cascade of particles produced by the high energy photon as it hits the atmosphere. This produces Cherenkov radiation which can then be detected by optical telescopes on the ground. Using telescopes such as AUGER and HESS, energetic sources such as supernova remnants, active galaxies, and nearby galaxies such as Centaurus A have been observed.

Mission Updates

JAXA's KAGUYA (SELENE) spacecraft has been orbiting the Moon since the end of 2007. The mission consists of a main orbiting satellite at about 100 km altitude and two small satellites (the Relay Satellite and VRAD Satellite) in a polar orbit. The mission has performed global mapping of the lunar surface, magnetic field measurements, and gravity field measurements. It has also sent back some brilliant HD movies from as low as 11 km above the lunar surface. The nominal mission came to an end in February 2009. Since then it has been working in an extended phase which will conclude when KAGUYA crashes into the Moon on June 10th 18:30 GMT. The impact will be on near side in "night-time area".

NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Spirit has far exceeded it's nominal lifetime of 90 days but is currently stuck in soft terrain on the west side of Home Plate. That hasn't stopped the plucky Spirit from taking lots of scientific measurements and panoramic pictures while it waits for the team on Earth to come up with a strategy to free it.

As Megan says in the news, Servicing Mission 4 to repair the Hubble Space Telescope has been a success. There is a great video filmed by astronauts inside Space Shuttle Atlantis as they release Hubble.

Anniversary of the 1919 Eclipse

In May 1919 Sir Arthur Eddington and the Royal Astronomical Society launched an historic expedition to observe a total solar eclipse. The idea was to test Einstein's Theory of Relativity by observing the light from background stars bent by the Sun during the 1919 eclipse. Researchers from the University of Oxford and the Royal Observatory Edinburgh have recreated the expedition and you can read about their trip on the 1919 eclipse blog.

The Night Sky

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the night sky during June 2009.

Northern Hemisphere

June is not the best month to see the sky from the Northern Hemisphere as it doesn't get too dark. At around 11pm, overhead towards the north, is Ursa Major. There is more about Ursa Major on the night sky pages. Moving southwards you first cross the constellation of Hercules which has a 'keystone' of stars. Two-thirds of the up the right-hand side of the keystone, binoculars will show a slightly fuzzy blob. With a telescope you see the magnificent globular cluster M13. Below Hercules is the thirteenth constellation of the zodiac, the not particularly prominent Ophiuchus. To the right of Hercules is Corona Borealis - the Northern Crown. To the right of that is the constellation Bootes with one very nice bright star - Arcturus. Rising in the east towards the end of June we have Cygnus the Swan, Lyra, and Aquila the Eagle. The bright stars Deneb, Vega and Altair make up the Summer Triangle. With binoculars move from Altair a third of the way towards Vega. This part of the sky is called the Cygnus Rift and is a great cloud of dust. In front of that cloud we see Brocchi's Cluster or The Coathanger. Below Ophiuchus we have Scorpius and Sagittarius (containing the Teapot). From the northern latitudes of the UK we don't see these constellations well and a better view is seen from further south.

Jupiter, lying on the boundary of Aquarius and Capricornus, becomes more easily visible this month as its elevation in the pre-dawn sky is getting higher - about 24 degrees above the horizon by month's end. It rises at about 01:00 UT at the beginning of the month and 00:00 UT by the end of June. One problem with observing Jupiter with a telescope when it is so low in the sky is refraction in the atmosphere. This shifts the different colours of light in Jupiters image by differing amounts, so giving a blurred image. Using a green filter will help considerably in giving a cleaner image.

Saturn is seen as twilight deepens lying in Leo - but somewhat below the main body of the Lion. Its magnitude is +1 - not as bright as usual.

Mercury reaches "Western Elongation" on the 13th June which is when it lies furthest in angle from the Sun and seen before sunrise. However its elevation will be very low, and binoculars will almost certainly be needed to spot it (NB before the Sun rises!) at magnitude +0.6 given a very low north-eastern horizon. Warning: make sure that you are very careful to only observe before the Sun rises as seeing the Sun with binoculars is very dangerous.

Mars still remains low in the pre-dawn sky this month but, as it rises increasingly earlier than the Sun as the month progresses, will become easier to spot. It has a magnitude of +1.2.

Venus is now visible in the pre-dawn sky. It will only lie 14 degrees above the horizon as the Sun rises on the first of June, so will be easier to spot later in the month. It is at magnitude -4.2 at mid month, just to the lower right of Mars.

The highlights this month:

- On June 4th Neptune is close in the sky to Jupiter. Given a transparent sky it should be easily spotted in 8 x 40 binoculars just half a degree away from Jupiter.

- On June 10th there is a chance to see a nice line-up of Saturn's brightest satellites.

- On June 19th, at 03:30 UT, Mars and Venus are below a crescent Moon.

- June is also a very good time to spot Noctilucent Clouds!

Southern Hemisphere

June is a great month to observe the night sky from the Southern Hemisphere. Towards the north you'll see Leo and Saturn above it. Towards the south is the most beautiful skyscape with the Milky Way arcing across the southern sky. Scorpius is above Sagittarius down in the south east. High up in the sky are Crux and Centaurus. Towards the south west is the beautiful region around Carina and Vela with the Eta Carina Nebula. Low in the south is the Small Magellanic Cloud and the Large Magellanic Cloud up and to the right.

Odds and Ends

Listener Kate MacLean and her daughter have started a Facebook group called Shine Down! to raise awareness about full cut-off lighting.

Several Jodcast listeners have been inspired to create episodes for the 365 Days of Astronomy podcast. RapidEye has created episodes about M3, Wolf Rayet stars and January's garnet star. Nik Whitehead has created a great episode all about the life of a proton.

On the Forum a list of astronomical abbreviations has been started by Jodatheoak, RapidEye, EarthUnit and leloup.

Finally, check out the Sixty Symbols videos (technically not a podcast as the videos are not included in the RSS feed) from the University of Nottingham.

Show Credits

| News: | Megan Argo |

| Noticias en Español - Junio 2009: | Lizette Ramirez |

| Interview: | Prof Mike Lockwood, Michael Bareford, Kerry Hebdon and Neil Young |

| Interview: | Dr Jim Hinton and Neil Young |

| Night sky this month: | Ian Morison |

| Presenters: | David Ault, Jen Gupta and Stuart Lowe |

| Editors: | Stuart Lowe and Sam Bates |

| Intro script: | David Ault (and William Shakespeare) |

| Segment voice: | Danny Wong-McSweeney |

| Website: | Stuart Lowe |

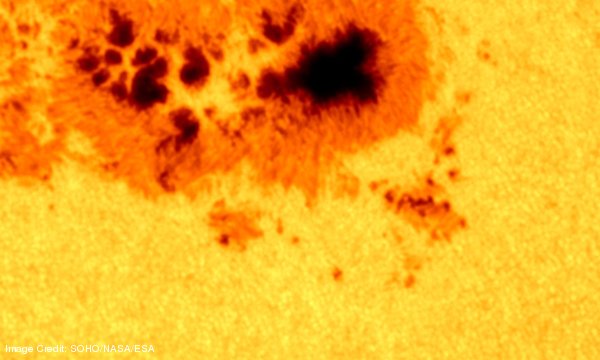

| Cover art: | Part of active region 9169 Credit: SOHO/NASA/ESA |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Noticias en Español - Junio 2009 [Duration 09:45]:

Noticias en Español - Junio 2009 [Duration 09:45]: